Demographics and the economy: how a declining working-age population may change Europe's growth prospects

Unpublished

(From ec.europa.eu)

© HUAJI / Shutterstock

According to Eurostat's demographic projections, Europe's working age population (aged between 20 and 64 years) will be declining by 0.4% every year between now and 2040, a decline that has already started in 2010. This will have major implications for the EU's growth potential in the long run.

Economic growth can come from two sources – and things are not looking too bright in Europe for either of them:

- Productivity gains (GDP per employed) in the EU have been lagging behind US labour productivity that grew by 1.5% per year since the beginning of the decade compared to around 0.9% in the EU.

- Employment growth in the EU is also trailing the US performance. Moreover, the 'demographic dividend' of the baby boomers (the fact that large cohorts born after WWII were of working age) is coming to an end and the working-age population will be shrinking over the next five decades – an unprecedented situation for the EU.

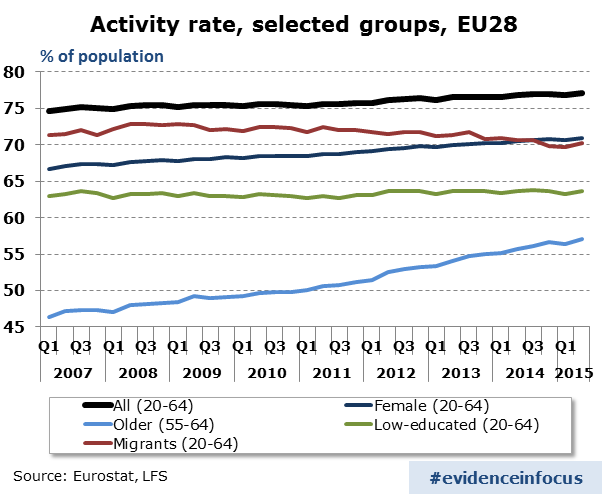

Activity rates very low for certain groups

The EU can, however, experience further employment growth even as the working-age population has started to decline. This is because activity rates of certain groups are very low as Chart 1 shows.

In spite of the shrinking working-age population and the sluggish recovery from the recession, labour force participation in the EU has been on a slight upwards trend, mostly thanks to higher female and older workers activity. In the latter case, a further extension of retirement ages beyond the age of 65 years is expected to have a positive impact also in the future. On the other hand, activity rates of low-educated people and third country migrants have stagnated or even fallen.

One can show that further improving labour-force participation is a necessity for Europe on its way to achieving its Europe 2020 employment target – and beyond.

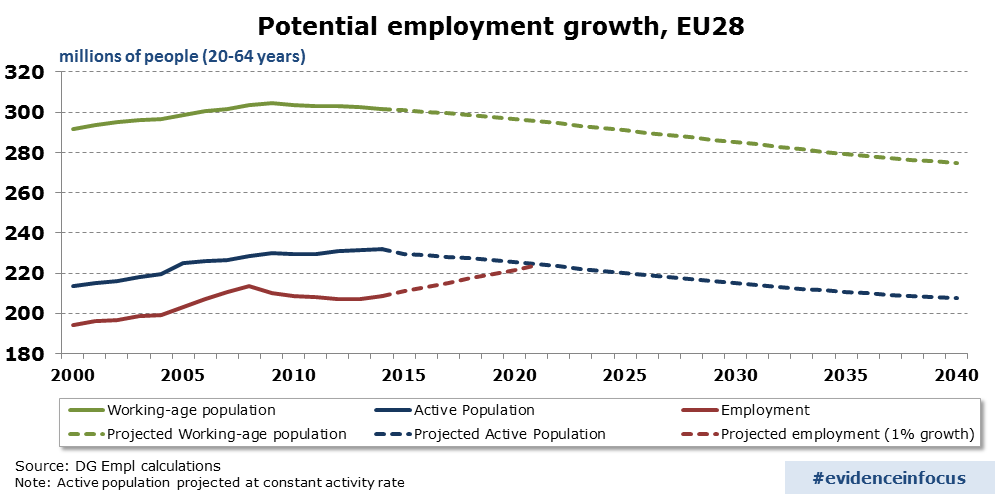

Limits to potential employment growth

Chart 2 shows working-age population as projected by Eurostat, together with the active population (which includes the unemployed) and total employment. It assumes that the Europe 2020 employment target will be reached: 75% of working-age population will be in employment by 2020. This would imply annual employment growth of +1% from now on, or 14 million jobs to be created in the coming five years. It would mean that the EU makes substantial progress in activating its so-far inactive human resources. Today, 23% of all people aged between 20 and 64 are not participating in the labour market.

If no further progress is made to better activate the EU's workforce, there will be strong limits to potential employment growth already towards the year 2020. Times will get particularly difficult after 2020 as working-age population will continue declining. A theoretical 1% employment growth path would have come to an end already shortly after 2020 if age-specific activity rates will not further improve from now on (constant activity rate scenario). With employment growth negative, one can show that the EU's productivity growth would have to double in order to keep the EU's economy growing at the same pace as it did before the crisis started.

One can also show that rising employment rates can only postpone the impact of demographics on employment. However, for employment growth to remain positive for as long as possible it is necessary to further increase activity rates. Improving the labour force participation of women, low-educated people, older people and third-country migrants will therefore have to be a priority.

A policy mix is needed

Future progress in the prosperity of the just over half a billion Europeans will require relieving the pressure on productivity. This includes a mix of the following measures:

- Pave the way to much faster productivity growth in the long run: Accelerate investment into human capital (education, training, skills) and promote research and innovation. Available research reveals that the EU lags behind the US in all these areas while other global competitors (China, India) are catching up fast. Structural change towards strongly growing sectors must be facilitated.

- Exploit all existing employment resources: As the working-age population shrinks, the EU must better tap into its existing human resources. The EU can no longer afford almost a hundred million people of working age being out of work, either unemployed or inactive. Higher intra-EU mobility can play a part in the strategy to increase employment and activity rates across all age groups. Currently, only 4% of the EU's working-age population is residing in another EU county, yet there is strong evidence that EU mobility helps to better allocate the EU's workforce across regions and sectors, and helps to reduce unemployment across sectors and regions.

- Open up for migration: Immigration from third countries can make a significant contribution to preventing the shrinking of the EU's labour force, but whether immigration translates into more employment and growth will depend on immigrants attaining higher levels of qualifications and skills.

Author: J. Peschner works as an economist at the unit of Thematic Analysis in the DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

Further reading:

- J. Peschner and C. Fotakis, Growth potential of EU human resources and policy implications for future economic growth, European Commission, Working Paper 3/2013.

- Demography Report, Short Analytical Web Note 3/2015, European Commission, DG Eurostat, DG EMPL, pp. 43ff.

- C. Fotakis and J. Peschner, Demographic change, human resources constraints and economic growth, European Commission Working Paper 1/2015 .

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which puts the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.