Different models of work and welfare in ageing Europe

Unpublished

(From ec.europa.eu)

Different models of work and welfare in ageing Europe

© Kinga / Shutterstock

Europe's population is getting older. As a consequence of this demographic trend and recent pension reforms that increased the statutory retirement age and curtailed early retirement options, the number of older workers aged 55 and above increased by more than 12 million between 2004 and 2014 in the EU28, bringing their total number to 38 million.

Yet, older workers still represent just over one sixth of all workers. A fast rise in employment rates of older workers and, implicitly, their effective retirement ages, will be crucial for ensuring adequate and sustainable pensions.

Comprehensive assessment of employment and social outcomes

A chapter in the recently published review Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015 examines the conditions of older workers across the EU and offers a comprehensive assessment of the situation of older people (see also our previous post on older workers as well as our post on active ageing).

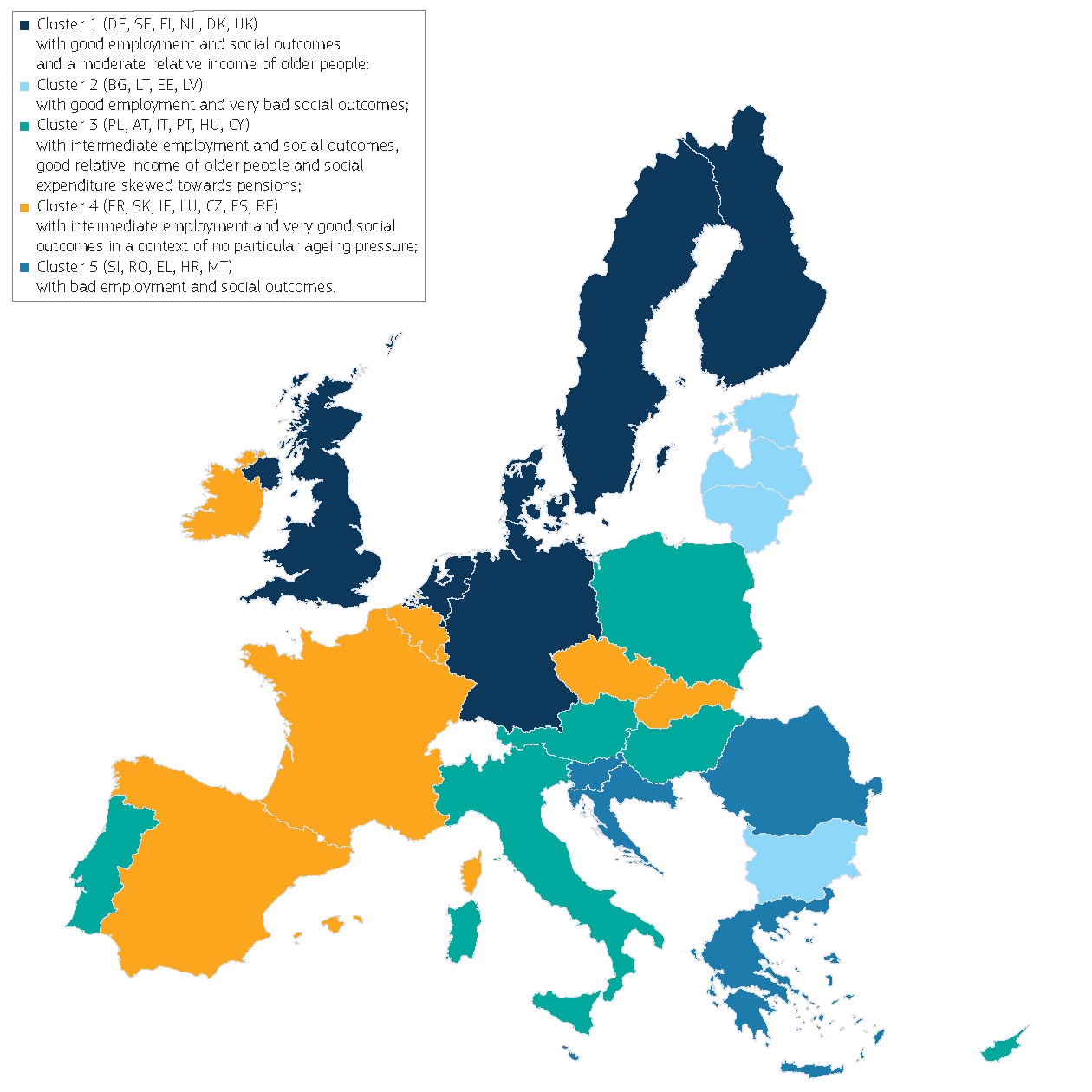

In the map below, Member States are grouped on the basis of a cluster analysis that considers three main dimensions. These are:

- The ageing pressure on social protection spending as measured by the old age dependency ratio and social expenditure on old age and survivors as a share of total social protection expenditure;.

- Labour market outcomes observed for older people (activity and employment rates and unemployment ratio between older workers and total working age population);.

- Social outcomes of older people including risk of poverty or social exclusion and inequality among people over 65 and the adequacy of pensions as measured by the ratio between the median income of retired people over 65 and employed people over 18.

Source: DG EMPL cluster analysis based on the most recent Eurostat data.

Source: DG EMPL cluster analysis based on the most recent Eurostat data.

Different approaches to ageing workforces: A mapping of Member States

Five different groups of Member States can be distinguished based on the cluster analysis. One group with relatively poor employment and social outcomes for older workers and retirees comprises Slovenia, Romania, Greece, Croatia and Malta.

The worst performers in terms of social outcomes can be found in another group consisting of Bulgaria, Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. Despite the good employment outcomes for older workers, these countries are characterised by very high levels of poverty and inequality among people over 65. The relatively high employment rates of older workers in these countries may reflect that people cannot afford to retire and have to work longer in order to have a decent income. In this case, working longer would just postpone the moment when people have to rely on an insufficient pension.

A more positive model of longer working lives can be found in the cluster that includes Germany, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Denmark and the UK. These countries perform well both in terms of employment and poverty or social exclusion. In these countries, work and social protection arrangements support working longer (e.g. flexible working hours and opportunity to work from home), and older people continue to work also for non-financial reasons. However, the relative income of older people in these countries lags behind that of the rest of the population. In addition, once unemployed, older workers face difficulties in finding a new job.

Creating an employment-friendly environment for older workers

Overall, despite the increase in older workers' employment rates during the crisis, their chances on the labour market are still not good enough when compared to the rest of the population. The general increase in the retirement age triggered by recent pension reforms has not made employers more willing to hire older workers. One of the main challenges remains to make older workers more attractive to employers. The increasingly skilled older workforce is likely to be an asset in workplaces, but age-discrimination still needs to be tackled.

Achieving longer careers requires a mix of different ingredients that would need to target both the older people themselves as well as the employers. Skilled and healthy older people are more likely to work, so preventing poor health and skills obsolescence is crucial, as are measures to help people juggle work and potential caring responsibilities. In addition, workplace adjustments and employers' attitudes matter in prolonging careers.

The chapter on older workers shows the huge untapped potential that older workers represent – and the challenge that many Member States still face when it comes to ensuring an adequate income in retirement.

Author: A. Fulvimari works as socio-economic analyst in the unit of Thematic Analysis in DG EMPL.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.