Part-time work: A divided Europe

(From ec.europa.eu)

Part-time work: A divided Europe

© www.BillionPhotos.com / Shutterstock

An increasing number of Europeans are working part-time. This can be a positive development if it means that people can choose more freely the balance between work and other pursuits – and between income and leisure – or if it brings employment opportunities to people who were previously excluded from the labour market: such as mothers, older workers, and students.

But part-time work also has a downside if it is involuntary or the only available option because of the difficulty of reconciling a 'standard' job with one's private life and family responsibilities. Working part-time can have costs beyond the loss of earnings compared to full-time working: part-time jobs are often of lower quality with lower hourly wages, provide poorer training and career opportunities, and, in the long run, reduce pension entitlements.

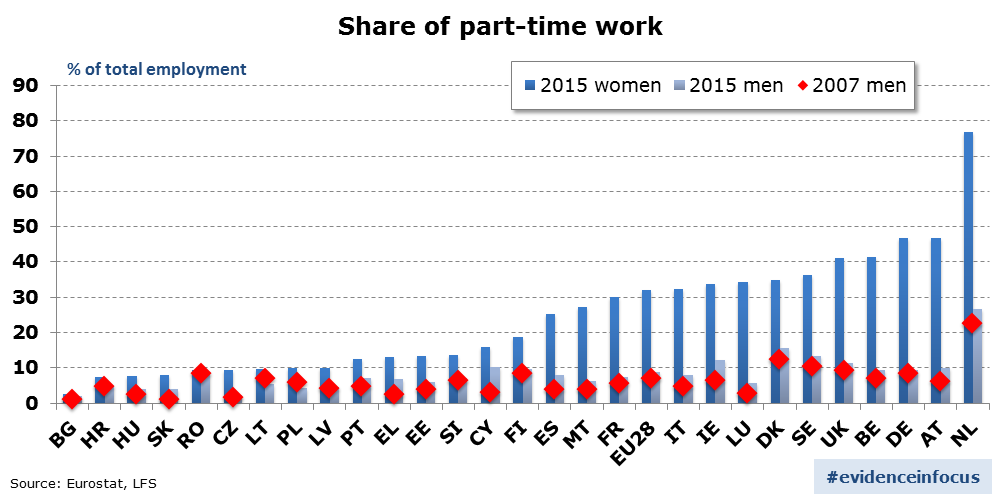

This blog post looks at the diversity of part-time working across the EU. The first striking observation is how gendered the phenomenon is. Far more women than men work on a part-time basis. In 2015, on average in the EU, 8.9 per cent of men worked part-time in contrast to 32.1 per cent of women, while the gap has been slowly closing.

There is also a clear East-West divide between countries: in Central and Eastern European countries part-time work remains a marginal phenomenon even among women, while the Western countries have embraced it much more widely.

A clear outlier is the Netherlands where three quarters of women work part-time, but also one fifth of men, almost three times as many as on average in the EU. The Netherlands also has one of the lowest shares of involuntary part-time workers. Reconciliation difficulties are likely to be an important driver of part-time working also in the Netherlands, but it also seems that there is more freedom for individual work/life choices and that this freedom is widely used.

Increase in part-time employment – and involuntary part-time work

In absolute terms, since 2007 part-time employment has grown in Europe, while full-time employment has declined. The share of part-time workers in the EU has increased in all but two countries (Croatia and Poland), on average from 16.8 per cent to 18.9 per cent. The increase has been especially strong among men: the share has almost tripled in Greece, Cyprus and Slovakia, and more than doubled in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Ireland, Spain, and Malta. The changes among women have been more modest.

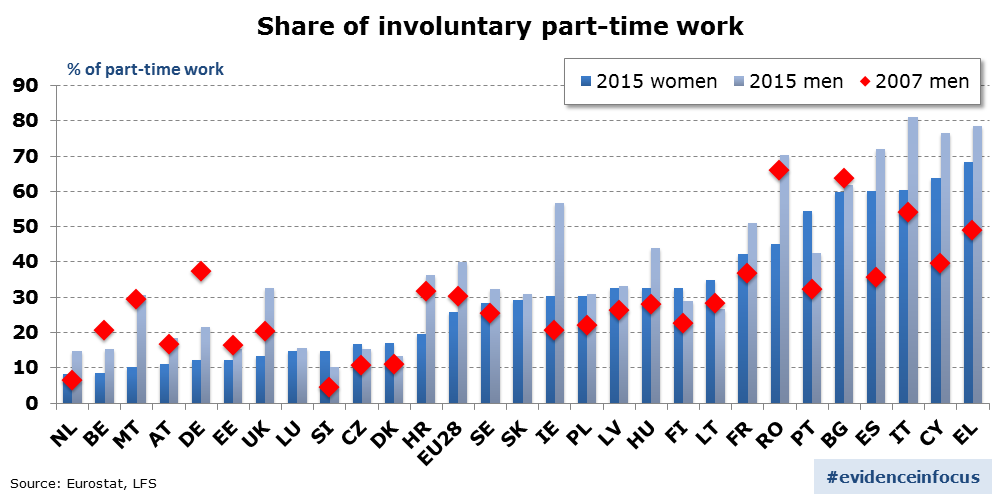

Unfortunately, this trend does not seem to be due to countries taking the Dutch path. Much of the increase is due to involuntary part-time work which has increased by a third, both among men and women. This means that people have taken up part-time work, or reduced their working hours, as full-time alternatives have not been available.

On average 23.1 per cent part-time workers reported to be working part-time involuntarily in 2007; in 2015 this share had increased to 29.9 per cent (with a slight decrease from 2014). For men, the share is higher than for women: 42.4 compared to 26.2 per cent. The share of involuntary part-time work is especially high in Southern countries where it has also increased significantly during the crisis (in Greece from 45.8% to 72.9%, Cyprus 31.2% to 69.4%, Italy 39.4% to 65.5%, Spain 33.6% to 63.7%). The strongest increase in involuntary part-time work took place in another crisis country, Ireland (from 11.5% to 39.2%).

The increase in part-time work can be a consequence of the economic crisis, especially in the worst-hit countries, but it remains to be seen if it is also the future of work and society. A pessimistic scenario would be that involuntary and precarious part-time work becomes the only option for more and more people. The optimistic scenario would present growing part-time work as a reflection of more flexibility and freedom of choice when it comes to the work/life balance – and this hopefully for both women and men.

Author: M. Vaalavuo works as a socio-economic analyst in Thematic Analysis unit of DG EMPL

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.