Mobile Workers and Migrants in the EU: Huge Untapped Potentials

(From ec.europa.eu)

Mobile Workers and Migrants in the EU: Huge Untapped Potentials

© hramovnick / Shutterstock

There is no doubt that immigration will stay high on the political agenda in the coming years – and it is important that the issue is debated on the basis of solid evidence.

A chapter in the recently published Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2015 review tries to provide some much-needed facts and figures.

It looks at opportunities and challenges of mobility and migration in the EU from the angle of economic growth: To what extent do intra-EU mobility and third-country migration contribute to growth today and what contribution could we hope for in the future? The main determinant for this is naturally their labour market performance.

How well are mobile EU citizens and migrants doing on their host country's labour market?

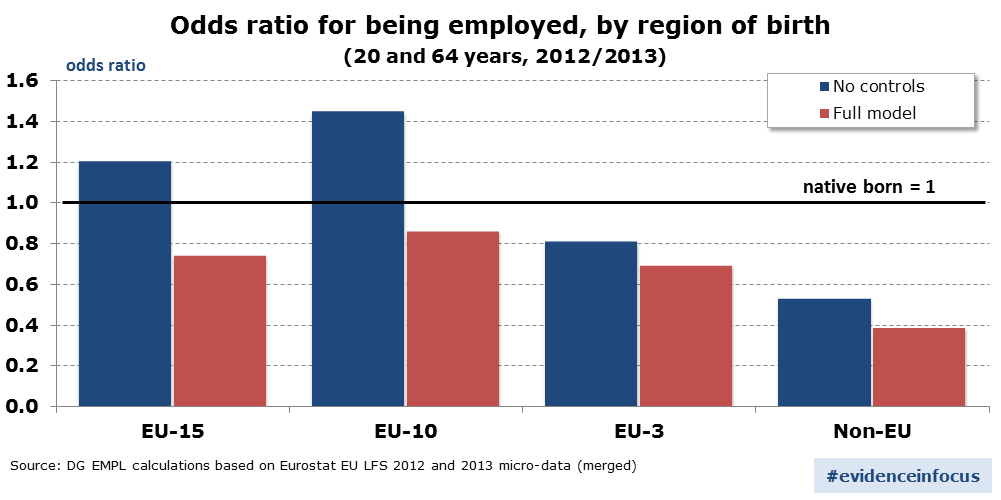

The chart above shows the odds (or the chance) for foreign-born people of being in employment, rather than being unemployed or inactive, compared to people born in the country. It considers four groups of foreign-born people. The first three groups consist of people who crossed intra-EU borders:

- those from the 15 'old' Member States which made up the EU before the 2004 enlargement (EU-15);.

- those from the 10 Member States which joined in 2004 (EU-10, which includes notably Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia);.

- and those from Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia (EU-3).

- In addition to the EU citizens, the fourth group are migrants who came from third countries, meaning countries outside of the European Union.

The performance of the native-born population is normalised to 1. The blue bar reflects the situation that is actually observed. If the blue bar is above the black line, this implies that this particular group of foreign-born people is more likely than the native-born to be in employment; if it is below, the chances of being in employment are lower than for the native-born.

EU-15 and EU-10 citizens more likely to be employed than natives, but…

The chart shows that mobile EU citizens from EU-15 and EU-10 Member States have a higher chance of being in employment than natives. The picture is very different for EU-3 mobile citizens and third-country migrants.

This may be due to people from EU-3 and third countries having individual characteristics that are known to reduce people's employment chances. These characteristics include age, education level, preferences for certain destination countries, and the family context. Using micro-data, it is possible to control for these factors and assume all of the four foreign-born groups had the same employment-relevant characteristics as natives. The result of this analysis is shown by the red bars which indicate the odds of being in employment after controlling for those characteristics.

Controlling for their personal characteristics actually reverses the result for EU-15 and EU-10 mobile citizens: They are now less likely to be employed than natives. This implies that the individual characteristics help a lot explaining these two groups' enhanced employability: on average they are younger and better educated than the native-born population and they are attracted to countries with labour markets that offer them good opportunities (e.g. the UK and Germany). This positive country selection effect improves their labour market performance. EU-15 and EU-10 mobile citizens doubtlessly improve labour allocation across the EU and help reduce unemployment for the EU as a whole.

EU-3 and third-country migrants face obstacles in accessing the labour market

For people from EU-3 and third-country migrants the situation is different in two ways: First, they stand a lower chance to be in employment than the native population; and second, controlling for their individual characteristics does not change the picture. Especially education does not make a difference at all for EU-3 mobile citizens and third-country migrants.

So what is it that prevents people from EU-3 and third countries from integrating successfully on the labour market? If it is not so much their characteristics, could it be the context in which they try to find work? A good education does not help much if there are legal restrictions, or if there is discrimination against migrants, or if employers don't recognise educational degrees obtained outside the EU. These factors are not directly observable in the micro-data. However, one can deduce from the observable data that they are likely to play major a role in explaining EU-3 mobile citizens' and third-country migrants' below-average labour market performance.

Also other disadvantages in the labour market for EU-3 citizens and third-country migrants

The chapter's other findings show that EU-3 mobile citizens and third-country migrants are also disadvantaged when it comes to finding a new job after having been unemployed or inactive. And those who do work are more likely to have non-standard contracts; they stand a higher risk of losing their job, are more often over-qualified for their job, and they tend to work in low-growth sectors. In addition, they have lower wages and suffer from higher dependency on social benefits due to their lower employment rates.

One can conclude that certain groups have problems to capitalise on their individual human capital on their host country's labour market. Member States fail to tap all available sources of growth – a great loss for individuals and society alike.

Author: J. Peschner works as an economist in Thematic Analysis unit of DG EMPL.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.