Poverty risks since the crisis: are older people winning at the expense of the young?

(From ec.europa.eu)

© Photographee.eu / Shutterstock

One of the legacies of the crisis is an increased number of people at risk of poverty. These are people with household incomes below 60% of the median income in their country. The share of people at risk of poverty (or the ‘at-risk-of-poverty rate’, AROP) increased from 13.5 per cent in 2007 to 15.9 per cent in 2014 among the working-age population (20-64 years old) – a rise of almost 20% (EU average excluding Croatia and Malta).

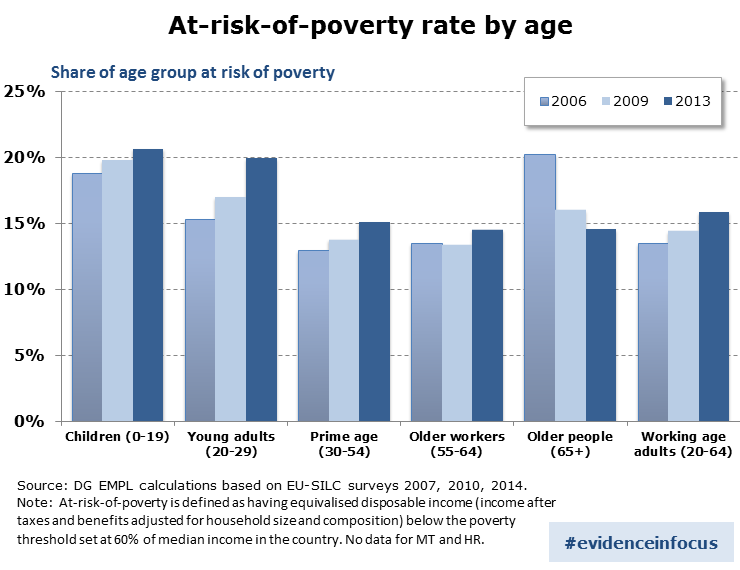

As the chart below shows, all age groups below 65 years experienced an increase in AROP, with those aged 20-29 worst affected. These young adults had their access to the labour market barred by a double-dip recession, and the AROP rate in this age group went up from 15.4 per cent in 2007 to 20.0 per cent in 2014.

The other age group that stands out are people over 65 years of age who saw their AROP rate decline from 20.3 per cent to 14.6 per cent, to a level below that of the working-age population. Poland, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and, to a much lesser extent, Germany are the only exceptions and recorded increasing AROP rates for older people.

There can be little doubt that young adults suffered badly from the crisis. A further increase in the AROP rate may well have been prevented by more young adults living with their parents rather than in their own households. The situation of the so-called Generation Y, or the millennials, i.e. those born between 1980s and 2000, has clearly become an issue of concern.

If young adults appear as the main losers of the crisis, can one say that older people are the winners? This is far from certain. The decline in older people’s AROP rates can be the result of pensions being more stable than other incomes. If incomes from employment and capital fall and pull down the median income, then an increasing number of older people may find themselves above the AROP threshold of 60% of the median income – without having more money at their disposal. The composition of this age group may also have changed as a result of large numbers of baby-boomers retiring. New retirees tend to have better pensions than the oldest pensioners, many of whom are women on low widow’s pensions.

Further analysis is required to understand what is behind this apparent reversal of fortunes between young adults and retirees, and how lasting it could be. However, it would clearly be also in the interest of older people that young adults see their situations improve very soon thanks to better labour market opportunities. Indeed, creating more opportunities for young people to be economically active is fundamentally important if we expect younger generations of tax payers to finance the pension and health care systems for the ageing population.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Editor's note: this article is part of a regular series called "Evidence in focus", which will put the spotlight on key findings from past and on-going research at DG EMPL.